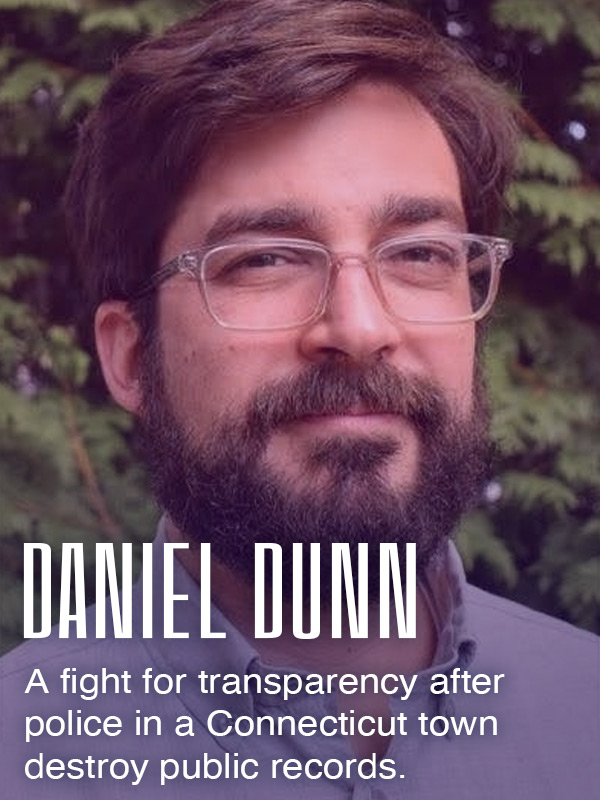

Our Right to Know: Daniel Dunn

A fight for transparency after police in a Connecticut town destroy public records.

By Sydney Sims

Doesn’t it seem a little strange to have a police oversight commission hosting public meetings behind closed doors in the police department they are expected to oversee?

Daniel Dunn thought so … even as a sitting member of said commission.

The goal of the Hamden (Connecticut) Police Commission, which Dunn – was appointed to by the local mayor, is to provide the citizens with the opportunity to oversee and hold the local police department to account. Dunn- always had an interest in the power of local government and its direct material effects.

After all, he had already been putting in freedom of information requests to various town government agencies for – things like financial data and employee salaries.

“More recently, I became interested in police accountability and what the police are even doing locally so as a citizen, I was making FOIA requests in my town just for various things,” Dunn said.

As a commissioner, Dunn says it was a natural progression for him to continue that work to get a grasp on the current state of affairs including complaints he was hearing from citizens about the commission’s lack of insight.

“It says in the town charter that the police commission shall hear civilian complaints, and historically, they hadn’t done that,” he said. “What is happening in our community regarding policing, what are these complaints? So, I made a request for all those records for a five-year period.”

He didn’t receive a law-abiding response. Instead, Dunn says the department sworn to uphold the law chose to break it.

“When I did that, the police destroyed them,” he said. “Or at least the physical copies of them. I learned by accident, through the town attorney, that the police had requested those records to be destroyed while my FOIA request was pending and the mayor signed off on it.”

Dunn says once he realized that the department and city had gone to extreme lengths to conceal records that potentially showed abuse of power within the department, in 2022 he filed a complaint with the Connecticut FOI Commission. He also hired an attorney to oversee the lawsuit.

“We took it to the FOI Commission, and the town ended up settling and admitted to a technical violation, “he said.

The smoking gun – the initial list of complaints Dunn says they used to stall his requests showed a mismatch of the records he actually received, proving that some of the records had been destroyed.

“It showed a mismatch…well, you said you had these and now you destroyed them,” he said. “Where is the ID of this complaint, right? They couldn’t match up on the one.”

Despite the settlement in 2024, which Dunn says resulted in a “victory without a victor”, the town admitted fault but paid no fines. The records still haven’t been recovered either.

“The Commission ruled in our favor to force the town to release a couple of records, but we settled where the town would basically admit fault,” he said. “But there was no accountability. The records were destroyed, and no one was held accountable.”

Dunn’s next steps have been focused on creating a public database where the information he received will live in perpetuity. The incident also inspired him to attend law school at Quinnipiac University.

Dunn says he still has an epiphany for fostering access between average citizens and the government, a right he says many don’t realize is extremely important for their day-to-day lives.

“A lot of people interact with their government all the time without knowing it,” he said.

“A lot of people interact with their government without their consent. And knowing what the government is doing is extremely important because we’re all paying for that.”

The New England First Amendment Coalition awarded Dunn with the 2024 Antonia Orfield Citizenship Award.